The Delvers of Dàrkmesa campaign rules represent the culmination of my ten years exploring the theory and spirit of tabletop roleplaying games in the vein of Dungeons & Dragons.

This project began in 2008 in the wake of D&D 4th Edition. But that inflection point needs some context.

I had been playing D&D since 2003, when a new friend gave me a copy of the 3rd Edition D&D Player's Handbook, having recently upgraded to 3.5 himself. I read every word in that handbook one thousand times over. I was running games of 3.5 for my friends soon after, and quickly settled into a nice groove: each campaign I tried to run would last three to four sessions, only to spiral out of control due to my lack of experience.

In my heart, I usually blamed the players for how things would fall apart. I had played the epic campaigns through in my head, and tried to run them all to that end. Didn't they know that Tolkien-level excitement and wonder awaited them, if they could just go along with the story? They never seemed to march to the tune, despite their best efforts. Luckily, we were young, and all still in school in our home town. Starting a new game every month was never an issue. I had a million tired fantasy tropes that I yearned to emulate at the table, and a good handful of friends more than willing to indulge me.

I never admitted that I blamed them, and that was good, because it was my fault and I didn't know it. I didn't know that the stories I liked to read and write were not the ones I liked to play in or run. I couldn't see that my campaigns as conceived were little more than setting and stage direction. It was truly the bliss (or perhaps, frustration) of ignorance.

You see, the friend that introduced me to D&D was the first person I ever met who played. That made me the second person I ever knew who played. Each of my other friends who I invited to play then became the third, fourth, fifth, and so on. We were making it up as we went. Sure, we were using the rules. But the rules don't tell you how to play. Not really. And back then, it was faster to walk to the library and check-out a Dragonlance novel than to look up anything online. How other people played was a complete mystery to all of us.

Around 2007, the older cousin of a friend of mine came to town. His name was (is) Nick, and besides being a math genius, he was also an avid player of 2nd edition D&D. Once he found out his little cousin and co were all playing D&D on the weekends, he offered to run a (3.5 converted) game of Ravenloft for seven or eight of us.

That was good D&D. I played a monk, which was a terrible class in 3.5. But the D&D was good, so I had fun.

Then we went back to playing our own games (which I ran), and they sucked again. I would often pine away in my memory for the details of that game, searching for its secret sauce.

In 2008, 4th edition D&D is released, and for the first time, the veil of design is peeled back for me. The deliberate ways that the game was laid out and organized, the brutal crackdown on the numbers, the every inch regulated and standardized.

D&D it was not. My friends all lamented the something that was lost in translation. I maintained always that I loved 4th edition, but found it rather hard to express precisely why in the language of fun. In my eyes, 4th edition was designed to a very specific end: tactical combat play. In that, it succeeded. It was designed to be learned quickly. Again, it succeeded there. It was designed to look modern and aesthetically consistent. A+ again. It was the right product, but for the wrong market.

So my theory crafting and homebrewing began. "There must be a way," I thought, "to bring the principles of design from 4th edition into 3.5 such that we can play a superior hybrid game."

It should be said: 3.5 was universally regarded as broken by 2008. How broken exactly was up for debate, but the sheer lack of direction for the design of the game and its splat books was becoming a malignant issue. There was too much game, and no central idea to measure each component's worth and validity against. One of the primary draws to a new game from the player's perspective was the chance to try out new classes and options. But from the other side of the table, every new feature was a chance to break the game.

Notebook after notebook did I fill with my Frankenstein D&D hacks. If I recall correctly, the first things I ever scribbled house rules about were skills and feats. Did we really need over 36 skills? And who knows how many hundred feats? Do those options really enrich play, or do they just tickle the fancy of min/maxers?

By 2009, my family had DSL and I had my own laptop for school. So I decided to start Googling these questions and delving for answers in the dark halls of the interweb.

What I discovered was called the Old School Renaissance. It had begun around 2006 or 2007, as best I can tell, with some bloggers connecting on various forums and posts. They shared ideas from their history with the game, which stretched back to its very beginnings, and even before. They knew the old rulesets weren't perfect, and offered their solutions to the age-old problems. There was debate and proselytism among great grognard philosophers, and countless quiet members of the community, like me, just trying to absorb it all.

These champions of the old school tore my fragile conceptions about D&D apart, like the Twelve prophets of the Hebrew Bible chastising Israel. What was this game I had been playing all these years? Where had it come from, and what great pillars of its history had been lost to its many transmutations? Had we taken the wisdom of its forefathers for granted? Nowhere else have I seen such thoughtful effort by people to justify their ideas about a hobby and its function. While everyone else spent three years learning Pathfinder, I was mesmerized by the mysteries of OSR games.

If this era (c. 2006-2011) was indeed the Old School "Renaissance," then what happened in 2012 was the Old School "Industrial Revolution." In January, Wizards of the Coast announced that the short-lived 4th edition would soon be replaced by a new D&D, "D&D Next." In May, they began a massive open playtest of the rules they were working on.

The forums that existed on the old WotC website containing all of the playtest feedback and discussion were truly a treasure of knowledge and design theory. I was well into my obsession with writing a better ruleset by 2012, and I consider myself extremely lucky to have had the chance to explore those million musings before they were archived later that year.

For two years, there seemed to be no word of the next D&D, but my mind never stopped swirling around the problems the OSR had illuminated. As I got further into college, time for playing the game became scarce, but my interest in thinking about it only grew. The homebrews I made became smaller and simpler. There were fewer and fewer rules each time I would revise or start again. I was getting better at the design, but deep down I still didn't understand what I wanted. I was designing for better design's sake, but not for the sake of better play. Indeed, most of my homebrews never saw the light of day. The ones I did test largely felt like playing any other ruleset.

It doesn't matter much what font you write the stage directions in, turns out.

In 2014, D&D 5 came out, and my friends loved it. It was the greatest thing since sliced bread, fixing all the problems with 3.5, but still holding onto that something that 4 had abandoned.

But when I looked at it, I was disappointed. Sure, advantage/disadvantage is a great mechanic. And yeah, the monk is way better now. And oh hey, they are consciously keeping the official splat books and feats and skills and classes under control. All good things, no doubt, for those of us content with the quality of play we had achieved throughout the years. But D&D 5 didn't do what I desperately wanted it to do.

It didn't show me how to design toward something. D&D 5 is the everyman's game. It's a story game, it's a tactical combat game, it's epic high fantasy, it's gritty low fantasy. It's everything, and nothing. At the table, it feels just like 3.5 did when my friends and I couldn't yet afford the extra books.

Fast-forward another year, and Critical Role is D&D's technological revolution. D&D is sexy now, and it rivals the best TV shows for hours of content and number of dedicated fans. Like all instances of celebrity art, Critical Role is at first inspiring, and then soul crushing. Inspiring because it shows you what tabletop RPGs can deliver, and soul crushing because I am not friends with a cadre of professional voice actors who want nothing more than to practice their acting around my narrative, with some combat thrown in to spice things up. It isn't just an unattainable ideal, it may actually be an un-approachable ideal depending on the friends you have.

A cursory scan of D&D subreddits these days will show you the Critical Role heartbreak phenomenon writ large. DMs are afraid to let their players fail. They're afraid to change the plans they have for their narrative in response to what the players do. They hand their players stage directions, and instead of amazing voice actors and improv artists, it turns out their players are just regular people. The story-based D&D facade all comes crashing down when you try to fit it into the real context that the game has in our lives. A weekly hobby for a handful of non-writers and non-actors with shifting schedules and more important things to remember than the evil motivations of the Demon Vicar of Nowheresville in your tabletop soap opera guest-starring the player characters.

But even a few years into playing and DMing 5e, I still maintained that top-down DM fiat narrative was a viable play strategy. And it wasn't until a little later, when one of my close friends ran a short-lived game in which I played, that the final trigger for my OSR metamorphosis would occur.

The setup was this: the party (which had several new members) were asked to convene at an inn to receive a quest from an NPC. We did, and the NPC told us how to get to a mythic dungeon full of (literally) civilizations worth of treasure. If we do it, the NPC gets to keep whatever scrolls and spellbooks we find in the loot. My guy is a fighter, so that is fine with me.

The party leaves for the dungeon, which is in the center of a crazy necrotic swamp that has emerged around it because the dungeon is the fossilized remains of an ancient dragon god (cool) which is causing the land to transform as it decays (super cool). When we arrive, there is a crew of evil dudes camping around the dungeon entrance, which we battle and defeat in a fight (sweet). Then, upon entering the dungeon, we find out that all of the treasure has already been looted and thrown through a portal into the plane of Limbo (...what?).

Now, from my friend's perspective, he was offering the potential for a sweet adventure on a rarely-explored plane of existence. And had that been the hook for the adventure from the beginning, I would have been more than excited.

But from my perspective, my character's motivation to adventure had been flushed down the drain. That might not be so bad (hey, things don't always turn out the way your character wants), but my poor dwarf was also trapped by the swamp. I tried to make a choice about what adventure my character would pursue, and then when that was turned on its head, I was denied a second choice. Not only was the original intent of the adventure no longer an option, but if my character jumped through that portal, there was literally no way for me to control whether I could turn back. No way for me to make an actual choice.

I was outraged after the fact, and it surprised me! This was no different than a hundred other times that one of my friends or I had weaved a D&D web around our players to get them to do what we wanted. The difference this time was how obvious it was to me given the mindset that I was in. I didn't blame my friend, I blamed our collective understanding of the game.

The swamp was not an obstacle to the treasure, because the treasure wasn't there anymore. The swamp was an obstacle to beginning the adventure, or any other adventure for that matter, if the party had changed its mind. The dungeon was the single source of player-DM agreement ahead of time, and it was thrown out. The foundational structure of the game, that there was a treasure to be had if some obstacles were overcome, was abandoned for the sake of an unsure reward (the treasure was in Limbo, after all) after an indeterminate amount of time and obstacles.

The contract of the game was broken, I was mad, and that was the answer I had always been looking for. What was the contract that my games should make between the DM and the players? Whatever that contract, design the game toward it.

D&D 5 makes no contracts. All forms of play are equally valid, and therefore there can be no measure of what games succeed or fail except on the scale of fun. This makes DMing, and DM prep especially, a nightmare of guesswork no matter how many books or tips or tools you have. What type of game will be fulfilling? What type of game will last? How do I get the players to ask about my availability to play rather than trying to chase them?

Well what if, given the wealth of OSR knowledge that I had absorbed, I made the contract of my campaign specific in the way that is time tested:

In this campaign, the player characters will explore a megadungeon for treasure. They will frequently return to the outlying town or towns to restock and rest, and may occasionally pursue non-dungeon adventures when the desire strikes them. New players and characters can come in or be swapped in at any point while the party is in town. No individual player needs to attend every session because no individual character needs to be on any given delve.

I, the DM, promise to prepare for that. The players promise to bring characters that will eagerly pursue that cadence of play. It doesn't create any unspoken requirements to attend every session for the sake of keeping in the loop of the plot. It doesn't mislead players as to what they will be doing. And most importantly, it takes a hard line on the boundaries of the play area, but within that play area, there is real choice with real consequence. No Quantum Ogre, no DM fiat.

And so, if I designed a ruleset around that contract, and DMed the game around that contract, I would be able to actually improve the game from session to session because I and the players would be pursuing the same goal. Which finally brings me to Delvers of Dàrkmesa.

Once I landed on the idea of the megadungeon as a distillation of the time-tested campaign promise, I thought about making my own take on Dwimmermount (if only for the supremely euphonic nature of the name), but decided instead to go completely homebrew. That's how Dàrkmesa came to be. I was struck by the double meaning of mesa (a huge rock formation that could easily fit a megadungeon inside, as well as the Spanish/Latin root for table), and what would a dungeon be without darkness? The Delvers part is just to drive the point home. Both in the sense that the characters will be primarily engaged in exploring a dungeon, and in the sense that the game is about them and about their exploration, not some arbitrary story I have concocted.

The rules and classes and example spells to include all fell into place now that I had a gameplay goal in mind other than "have fun." Many of the strangest parts of old school games that I could never understand before started to make sense and became incredibly attractive aspects of the experience for me.

Of course the game should be deadly, because that is a large part of what creates drama in a campaign with no forced plot. Of course random encounters were necessary, to keep the players and the DM honest as they all pursued the campaign goal: random chance is what keeps a non-narrative game alive. Of course two hundred pig-faced orcs appearing in a dungeon cavern is a good encounter, because it forces the players to bring to the table what makes them good players, not well-statted characters. And finally, of course the dungeon is the primordial soup from which all good games emerge, because it is the most apt compromise between what the DM needs to do, and what the players need to do. It creates strict boundaries that allow the DM to prepare more of the right thing, but when done right it forces no specific action on the players other than to engage. They want the treasure, and however they get it is by definition a fine way to play. That's why we all play this game, to get the treasure that exists hidden in the forgotten halls of our collective imagination and good company. So why hide the ball? Why not be clear about how agency works in the game right from the beginning? Why not embrace the canvas that was originally conceived for the game, and was so important that it became the first word in its name?

Luckily, it only took me ten years of searching to figure that out. Now I have the rest of my time to play.

Showing posts with label player psychology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label player psychology. Show all posts

Sunday, February 17, 2019

Saturday, March 4, 2017

Disappointing Combat in D&D

SPOILER ALERT: I'm writing this while watching the newest episode of Critical Role (ep. 88). If you don't want to have minor combat details ruined for you, wait to read this until you've seen the episode.

Read at your own peril.

--

In this episode, the party engages in an underwater battle with a kraken. The setup is short but sweet, and then, as much D&D combat is want to do, the play slows to a crawl as soon as initiative is rolled.

Now, given that this is all submerged, I understand slower movement speed. But that's not what is going on here. Each player's turn takes one of two forms:

1) excruciatingly long because they are trying to figure out how the rules apply to the unique circumstances.

2) breathlessly short because they are grappled and fail to escape.

The short turns are effectively not turns at all, they are just more pauses in the action. Here is an example of an excruciating turn: Grog is swallowed by the kraken and he is blinded, restrained, and slowly burning in acid. When it comes to his turn, he doesn't have anything to do but "swing his weapon" to deal damage to the kraken from the inside. Of course, the whole reason he is restrained is because he is being squeezed by the kraken's insides. He doesn't have nearly enough space to swing an axe or hammer, but because the rules tell him he can do nothing else, he is forced to make nondescript attacks that don't reflect the narrative reality at all. Needless to say, the turn is slow and uninteresting.

Worse than that, it's how you are supposed to escape. If you deal enough damage to the kraken from the inside, you might get puked out. But as we've already established, that makes little to no sense. Like I've said before on this blog, if there is a rule for how to do something, people are much more likely to use the rule rather than make something up, even if the rule is lame. We think within the box most of the time.

I can't think of an opportunity for more dynamic and exciting play than when a player in swallowed whole by a huge creature. Unfortunately, that's not what happened on that turn or the next. It took an incredible leap of logic by Grog's player to pull out his magic jug that makes oil. Then, when Keyleth the druid is also swallowed immediately after, the big risk of setting off a fireball and purposefully igniting the oil in the jug pumped life back into the encounter. The kraken pukes them back up and the real battle begins.

About an hour later, the real battle has ground to a halt again (before the actual encounter ends) and it becomes a game of how to escape through a portal when everyone keeps getting grabbed and restrained by the kraken. The party's goal is to leave without killing the beast, but it's "stickiness" and the underwater environment make this goal extremely difficult. After several rounds of the party trying to break free and getting pulled back, Vax the rogue is swallowed while unconscious.

This is followed by another grueling turn for poor Keyleth who is barely able to keep the all the alter-self, animal shapes, and druid beast-shapes straight.

The issue here is not Critical Role, the players, or the DM. It's the rules. The rules are designed in such a way as to punish any "get-in-get-out" encounters. Every enemy is sticky in D&D, and the kraken is the king of sticky things. It has two average parties-worth of tentacles which auto-grab and restrain after dealing damage on a hit. The party members that are restrained lose approximately a third to a quarter of all their actions during the fight. They just fail their escape rolls and do nothing. That's not even counting the swallow ability, which is essentially a nigh-inescapable grapple.

It's painful to watch the party members on screen look utterly exhausted by their lack of options. The combat ends in an intense way, but that's all thanks to the roleplaying and DMing that are superb. They were succeeding in entertaining themselves (and us viewers) in spite of the rules, rather than with them.

I haven't thought about D&D from a design standpoint in a while, but these same issues are always on my mind when I do. There's got to be a better paradigm for handling combats like this, where everything devolves into repetition of two or three optimal actions until math saves the day for one side or the other.

Read at your own peril.

--

In this episode, the party engages in an underwater battle with a kraken. The setup is short but sweet, and then, as much D&D combat is want to do, the play slows to a crawl as soon as initiative is rolled.

Now, given that this is all submerged, I understand slower movement speed. But that's not what is going on here. Each player's turn takes one of two forms:

1) excruciatingly long because they are trying to figure out how the rules apply to the unique circumstances.

2) breathlessly short because they are grappled and fail to escape.

The short turns are effectively not turns at all, they are just more pauses in the action. Here is an example of an excruciating turn: Grog is swallowed by the kraken and he is blinded, restrained, and slowly burning in acid. When it comes to his turn, he doesn't have anything to do but "swing his weapon" to deal damage to the kraken from the inside. Of course, the whole reason he is restrained is because he is being squeezed by the kraken's insides. He doesn't have nearly enough space to swing an axe or hammer, but because the rules tell him he can do nothing else, he is forced to make nondescript attacks that don't reflect the narrative reality at all. Needless to say, the turn is slow and uninteresting.

Worse than that, it's how you are supposed to escape. If you deal enough damage to the kraken from the inside, you might get puked out. But as we've already established, that makes little to no sense. Like I've said before on this blog, if there is a rule for how to do something, people are much more likely to use the rule rather than make something up, even if the rule is lame. We think within the box most of the time.

I can't think of an opportunity for more dynamic and exciting play than when a player in swallowed whole by a huge creature. Unfortunately, that's not what happened on that turn or the next. It took an incredible leap of logic by Grog's player to pull out his magic jug that makes oil. Then, when Keyleth the druid is also swallowed immediately after, the big risk of setting off a fireball and purposefully igniting the oil in the jug pumped life back into the encounter. The kraken pukes them back up and the real battle begins.

About an hour later, the real battle has ground to a halt again (before the actual encounter ends) and it becomes a game of how to escape through a portal when everyone keeps getting grabbed and restrained by the kraken. The party's goal is to leave without killing the beast, but it's "stickiness" and the underwater environment make this goal extremely difficult. After several rounds of the party trying to break free and getting pulled back, Vax the rogue is swallowed while unconscious.

This is followed by another grueling turn for poor Keyleth who is barely able to keep the all the alter-self, animal shapes, and druid beast-shapes straight.

The issue here is not Critical Role, the players, or the DM. It's the rules. The rules are designed in such a way as to punish any "get-in-get-out" encounters. Every enemy is sticky in D&D, and the kraken is the king of sticky things. It has two average parties-worth of tentacles which auto-grab and restrain after dealing damage on a hit. The party members that are restrained lose approximately a third to a quarter of all their actions during the fight. They just fail their escape rolls and do nothing. That's not even counting the swallow ability, which is essentially a nigh-inescapable grapple.

It's painful to watch the party members on screen look utterly exhausted by their lack of options. The combat ends in an intense way, but that's all thanks to the roleplaying and DMing that are superb. They were succeeding in entertaining themselves (and us viewers) in spite of the rules, rather than with them.

I haven't thought about D&D from a design standpoint in a while, but these same issues are always on my mind when I do. There's got to be a better paradigm for handling combats like this, where everything devolves into repetition of two or three optimal actions until math saves the day for one side or the other.

Saturday, July 16, 2016

5 Goals Your NPC Organizations Shouldn't Have

There are three types of NPC groups in fantasy RPG worlds:

- Groups the PCs can fight. Example: the cult of an evil demon lord.

- Groups the PCs can receive service from. Example: a merchant guild.

- Groups the PCs can join. Example: giant-slayer mercenaries.

No DM has trouble with the first group. They are the easiest to think-up and use in the game.

The second group is easier than the first, in that their motivations need not be world-shaking or nuanced. They can just be a trading band, after all. But they are also more difficult than the first group, because it is much less natural to roleplay a merchant than an evil cultist, considering how scant merchants are in most fantasy novels and D&D plot-lines. It's very similar to writing: the mundane stuff is the hardest to make believable because you haven't ever given much though to it.

Where many D&D worlds fail, however, is with the third group. I'll give you some examples.

Black-Flame Zealots: If these aren't the coolest divine group ever, I don't know what is. They are Assassin's Creed meets ninja meets Nepalese holy-warrior. If there was a novel or video game about these guys, I'd buy it in a heartbeat. Unfortunately, they are a clandestine order of monks who work primarily out of city hideouts and only battle with the enemies of their god. They are like a thieves guild, but with more smiting and less casual sex.

How in the world do you DM a PC that is a member of this group? How do you convince the PC that going off to a random dungeon and looking for treasure is a reasonable quest given his profession? If an old lady says she has ROUSs in her basement, why on earth would a member of the BFZs offer to help her? Don't they have a dark god to keep at bay?

How about the Cavaliers? Mounted soldiers? Really? That's the kind of character you are going to play in this dungeon-crawling game? One who needs a horse at all times to have any fun?

The deeper you dig into all these supplemental classes and groups, the more you realize that over half of them cannot be played.

Sure, you can take the Purple Dragon Knight prestige class from 3.5's Complete Warrior, but take a look at their description, and the paragraph-long disclaimer about player-character members...

|

| D&D 3.5, Complete Warrior, p. 70, Wizards of the Coast |

In the end, a PC Purple Dragon Knight has no rank, no authority, no experience, no service record, no commitment to future service, nothing. They have nothing but an honorary title and a slew of class abilities that seemingly appear out of nowhere, given how little the PC actually has contact with their affiliate group...

These disclaimers are included because the designers know that players want the cool features and titles, but none of the responsibility. The PCs still plan to explore and search for treasure and kill monsters as their primary lifestyle, so being a full-time (or even reserve) member of some army is not on their to-do list.

And why should it be? This is Dungeons & Dragons, not Soldiers & Sergeants. If you want to play a medieval warfare simulator, play one. D&D is not that.

This is a reality that DMs and PCs need to accept: limit yourself so you can focus your game and do it well. Players don't need access to infinite character concepts to have fun, they need access to a handful of character concepts that fit the world and the tone the game is going for. DMs don't need infinite NPC groups from every walk of life, they need a couple dozen groups, the majority of which should be adventuring groups that PCs could easily join while still maintaining their normal day job.

There are a million reasons why an NPC group would be invested in dungeon-crawling and monster-slaying. I'll put a bunch into a blog post sometime. But until then, here are five goals your joinable NPC groups shouldn't have, because they create direct contradictions with the adventuring lifestyle:

1. Operate in a particular area, e.g. a specific city, forest, or even country.

If the PCs ever want to leave, either the PC members have to quit, get some sort of negotiated leave time, or create a convoluted reason for why it is relevant to the Elvish Defenders of Leafwood that Joe the Ranger go off into a desert and dig up some magic scrolls about turning lead into gold.... These groups are type one or type two: enemies or service providers.

If the PCs ever want to leave, either the PC members have to quit, get some sort of negotiated leave time, or create a convoluted reason for why it is relevant to the Elvish Defenders of Leafwood that Joe the Ranger go off into a desert and dig up some magic scrolls about turning lead into gold.... These groups are type one or type two: enemies or service providers.

2. Research a particular thing unrelated to dungeons, e.g. feywild specialists, divination experts, very specific monster-hunters, etc.

This shouldn't be confused with something like a weapon-specialist group. I'm talking about any group where actively adventuring would cut into their study time, rather than be study time. Sword masters-in-training can hone their skills anywhere, but students of Fey lore have nothing to learn while infiltrating the underground city of the Derro. These kind of academic groups are also type two.

This shouldn't be confused with something like a weapon-specialist group. I'm talking about any group where actively adventuring would cut into their study time, rather than be study time. Sword masters-in-training can hone their skills anywhere, but students of Fey lore have nothing to learn while infiltrating the underground city of the Derro. These kind of academic groups are also type two.

3. Serve a particular (non-deity) leader or country, e.g. a king or empire.

Unless he is the king of dungeon exploration, I don't want to hear about any PCs being in the kingsguard.... These are type one and/or two.

Unless he is the king of dungeon exploration, I don't want to hear about any PCs being in the kingsguard.... These are type one and/or two.

4. Pursue sedentary or mundane professions, e.g. blacksmiting, fishing, etc.

You don't have time to smith while you are slaying dragons and stealing their treasure, so smiths don't do that stuff. They stay home and smith. If you are a smith, you aren't a PC. If you are a PC, you aren't a smith. No ifs, ands, or buts. Type two again.

You don't have time to smith while you are slaying dragons and stealing their treasure, so smiths don't do that stuff. They stay home and smith. If you are a smith, you aren't a PC. If you are a PC, you aren't a smith. No ifs, ands, or buts. Type two again.

5. Enact a modern moral or ethical sensibility.

I'm not saying every group should be made up of assholes, but if your PCs come across the Loving Sisters of Peaceful Coexistence, do NOT let them join. Peace and non-violence are for farmers, not adventurers. Sad but true. The players can agree with their message in spirit, but they have to realize that their entire lifestyle (i.e. the entire game) is premised on violence and stealing, whether it is against other sentient races, monstrous races, or just plain ol' monsters. Evil in D&D is real, and it is out to get you. Monsters exist, and they don't only attack when threatened by oil spills or aggressive human expansion. And since the monsters are evil, might as well take their stuff when their dead. Right? Peace can be an ideal in your world, but it cannot be the mainstream. This could be type one or two.

Now go make some NPC groups that love spelunking and looting. I'd join that shit...

I'm not saying every group should be made up of assholes, but if your PCs come across the Loving Sisters of Peaceful Coexistence, do NOT let them join. Peace and non-violence are for farmers, not adventurers. Sad but true. The players can agree with their message in spirit, but they have to realize that their entire lifestyle (i.e. the entire game) is premised on violence and stealing, whether it is against other sentient races, monstrous races, or just plain ol' monsters. Evil in D&D is real, and it is out to get you. Monsters exist, and they don't only attack when threatened by oil spills or aggressive human expansion. And since the monsters are evil, might as well take their stuff when their dead. Right? Peace can be an ideal in your world, but it cannot be the mainstream. This could be type one or two.

Now go make some NPC groups that love spelunking and looting. I'd join that shit...

Thursday, June 30, 2016

How to Escape the Railroad D&D Game: Get off at a station

Quick announcement: Haven't posted in a while (got a full-time job), but plan to keep posting as often as possible. Will most likely shift my focus from game system design to adventure design, as that is where my head is right now.

____________________________________________________________

"Some players, Mr. DM, just want to watch the world burn."

- Someone afraid of sandbox games

"Players don't panic when things go according to plan. Even if the plan is horrifying."

- Someone afraid of railroad games

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

"Some players, Mr. DM, just want to watch the world burn."

- Someone afraid of sandbox games

"Players don't panic when things go according to plan. Even if the plan is horrifying."

- Someone afraid of railroad games

____________________________________________________________

Oh that unanswerable question: railroad, or sandbox? So short, and so mystifying. Within its seemingly binary choice are paradoxes and contradictions enough to fill entire college courses. See: Free Will vs. Determinism.

But let's boil the idea down to this: every DM wants their players to feel as though they are making choices that impact the world, but how do you do that without needing to literally create an entire world spontaneously?

Some will argue that you make a little "sandbox" and let the players do whatever they want in that little area. Easy. My response is this: even generating a tiny area that is a "free-roam" zone for the players is an unimaginably huge task. The idea doesn't ever scale down. PCs can cover a lot of ground in one session. You can't pre-generate all those possible paths, even in a very limited sandbox. And if you're thinking, "you don't generate everything the PCs can do, just the things they are likely to do" I say, welcome to a railroad game....

Meanwhile, if your argument is that you create some basic details and improvise the rest, you've entered into a similar paradox. If you magically incorporate your details into any path the PCs take, then you are running something VERY close to a railroad game. Best described as the "Quantum Ogre" effect. On the other hand, if you are willing to entirely abandon what you have prepared for the sake of maintaining player agency, then why prep at all? What are the odds that your players will choose exactly what you have prepared for them without railroading them at all?

To further confuse things: For every player that will purposefully avoid a pre-built story for something they think will be more exciting, there is a player who will do the opposite: ignore any hook or moment of inspired DM roleplaying for the never-ending slog through what they see as the "story."

The only way to appease both of these player types is to give the entire decision process over to the players, and then hold them to their choices. Your game must have cause and effect relationships, or the "watch the world burn" types will have no boundaries. Just so, the game needs to have very regular moments of choice, or the "go with the plan no matter what" types will quash everyone's creativity.

Okay, enough theory. Let's talk about putting this into practice.

Step 1: Prepare shit. There are no two-ways around it. You have to prepare sessions if you are going to give them any substance. Dynamic combats with interesting monsters, unique NPCs with believable spots in your world, competent antagonists, and many other parts of great D&D only thrive in the pre-game creative process. Maybe your random tables, acting, and improv are so good you don't really need to prep. If that's the case, I hate you.

Step 2: Accept that session 1 is railroad-y. Every D&D party has to suspend disbelief for long enough to accept that they are together, that they are at least allies in some respect, and that they will continue to work together until further notice. This is not an easy narrative step when your players are supposed to be brimming with "free will" and "agency." As the DM, you have to put your foot down and tell the PCs, "Welcome to session 1. Your characters are are all gathered in ______ for _______ and are planning to do _________. Go." Get the game going, regardless of whether every player is 100% into the mini-plot you have for the first session.

Step 3: Everything in the world has space for a hook. You have to bake hooks right into the body of your game world. Every corner should conceal another hook. But you need to expand your definition of what a hook is. Magic items are hooks. (What is it? Who can tell us? Where are they?) Information is a hook. Overheard conversations. Letters. Gossip. Everything. (The baron's raising an army? Why? Where? Someone mentioned the God of Socks. Who is that? Where can we learn about such a deity?) People are hooks. The dark spells cultists use are hooks. Statues are hooks. Paintings are hooks. EVERYTHING CAN BE A HOOK. Write a sentence for each good one you think up, and remind your players that these hidden treasures of adventure are everywhere if they pay attention and ask questions.

Step 4: Pace your sessions correctly. This will end up being a whole other blog post, but the short version is this: be smart about how long to spend on things around the table, and when to initiate them. Big combat after 4 hours of roleplaying session? Probably a poor idea, especially if it's getting late. Remember: you can always stretch things out with good roleplaying and description. You cannot, however, speed things up arbitrarily. When players focus on something, the time management is under their control. Prepare enough content to fill 50-75% of your session, then stretch it as needed.

Step 5: Finish your sessions at a choice, and have the players make it before ending. This makes #4 doubly important, because step 5 depends of successfully executing step 4. Each session should contain minimal "choice" points at the beginning and middle, because the more your players can veer off the path mid-session, the harder it is to make that session tight and satisfying. BUT, a major choice about what to do next that is placed at the end of a session allow players to tell you exactly what to prepare for next time. This choice point doesn't have to be "multiple choice" either. It can be "open response." So long as you have a week to prep what the PCs choose to do, they can do anything they want. Now THAT is agency.

Hooks are not choice points unless the players have nothing more urgent to do. Hooks can be kept in the back pocket of the party until some adventure time is freed up. This maximizes player agency, because it allows the players to choose the next part of their story organically, based on what most interests them about your game world. Free yourself from the trap of the escalating railroad campaign! You are better than that!

But let's be real: at the end of the day, even this style looks like a railroad. Pre-planned sessions that the PCs can't really change much once they are prepped by the DM.

But railroads can take you anywhere. Railroads (in the sense of pre-prepared sessions and stories) only become constricting when the players get an urge to jump off mid-way between stations. Solution: put in more stations. One at the end of every session. Keep the sessions focused and let them flourish into more depth instead of more plot if you have extra time in the moment. Your players will naturally want to follow mini-stories and plots to their immediate ends. Keeping players focused on a plot for one session is not an impossible task.

Trying to milk that one major player choice for three or four sessions of material is asking for trouble.

Wednesday, May 18, 2016

Sneaking Around In Tabletop RPGs

Stealth checks are a mess. I have yet to meet or hear of a GM that actually uses stealth checks in any deterministic way when it involves more than a single "sneaker." Party stealth is the most common kind of stealth check made, and as far as I have experienced, the party just needs to roll a rough average above the difficulty to avoid detection. Like a skill challenge a la 4E. How else could you actually do it?

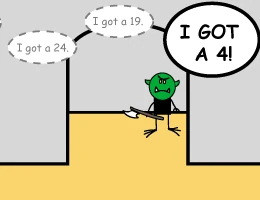

|

| From OOTS #90 |

This bears mentioning, because we have all snuck up on our parent, sibling, friend, etc. in real life, and scared the ba-jeezus out of them. Sneaking up on someone who is not paying attention to their surroundings is actually pretty easy. Even cats and dogs, with their superior animal senses, can be scared out of their furry wits by a sudden jump from around the corner.

So why does the game assume you will alert your enemies to your presence most of the time, if you let the fighter or cleric anywhere in their earshot? Surprising the enemy shouldn't be so much about silence as about timing.

Take the Siege of Osgiliath, for example. Regardless of how the build-up was shot (which I feel left a lot of tension to be desired), the great thing about this scene is that the Gondorian soldiers still manage to get the jump on the orcs by hiding just inside the entrance, despite half of them having plate armor. They get a surprise round, even though the orcs know full well that there are enemies inside the walls. In fact, a lot of the stuff about this scene that bugs people actually would make for great rules-of-thumb around the table.

Yes, plate mail rings like a bag of tin cans and wind-chimes when you fight in it.

But, there is always some kind of white noise going on that will lessen the odds that someone who isn't actively listening for sounds notices a person in plate mail walking carefully.

Yes, soldiers run across the orcs' line of sight like, a dozen times just before the boats dock.

But it is dark and misty and foggy and the GM has to be honest: the orc saw a shadowy figure dart across the entrance. They know that Osgiliath is occupied, but they haven't heard any war horns. Does that really give them enough information to avoid the ambush? I don't think so.

It is a strange vestige of incorporating perception and stealth checks into the game that many GMs and players operate under two very unrealistic and paradoxical assumptions:

1) That nearly every non-living, physical detail about the world is shrouded in some kind of impenetrable fog or obscurity until such time as a good perception check is rolled.

2) That nearly everyone is fully aware of each living creature within eyesight and earshot until such time as a good stealth check is rolled against them.

Those assumptions lead to this being part of every D&D session ever:

(GM) "You guys begin trekking through the woods"

(Players) "We all go stealthily" *rollrollrollroll*

(DM) "Uh...yeah, okay you go pretty quietly on your way"

How is this even a thing? You roll one stealth check each for a whole day of travel, when earlier that day the rogue had to roll a whole stealth check just to take two steps behind an orc without it noticing? That's like saying the fighter can get through a whole day of random encounters with one attack roll, but has to roll for every attack when he encounters a pre-planned fight.

Are your characters seriously checking behind every tree and around every hill and padding every footstep to avoid contact with sentient beings? Or are you just keeping your voices low and going slow? Cuz you shouldn't need to roll for going slow, bro. Slowing down and shutting up is easy.

Are your characters trying to move fast, but not alert anyone? Tough shit. You get one or the other, unless you have some bombdotcom spell you wanna blow for super quick silent movement, or you are a high level ranger with some class feature that gives you crazy stealth stride. It is a basic fact of life, and one that needs to be preserved to have an interesting and problem-solving oriented adventure game: the faster you go, the louder you are and the more likely someone will notice you. The slower you go, the easier it is to move about without drawing attention to yourself.

Stealth is probably one of the wonkiest mechanics simply because it exists as the veil between the free-range character action outside of combat, and the turn-based character action inside of an encounter. Some might think of initiative when I say that, but initiative is "Step One" of combat, not the connecty bit. If you fail your stealth check, typically, combat begins. Maybe the target starts running away, maybe they pull out an axe and start swinging, who knows. Either way, it's now a two-player contest, and turns start being taken. If you succeed on Stealth, you remain the only "turn-taker" in the game, which means it isn't even a contest yet. No combat. Yet.

What would happen if we relaxed the combat structure of hard turns in a specific order, and instead made use of stealth merely as a means of getting the element of surprise on your side? In movies, for instance, when the action hero gets the drop on the guard guy, the hero snaps his neck or muffles him and slips a blade betwixt his ribs and that's all she wrote. In D&D, anyone but the rogue has almost no chance of taking the unsuspecting guard out in one-shot, because once combat rules kick in, damage is supposed to happen in little chunks over a long period of time. I don't see why the fighter couldn't shove his longsword through a dude's back and take him out (perhaps not dead, but certainly down), regardless of his HP. But again, if your combat is very rigidly segregated from your "non-combat" play, then it will be hard to justify anyone but the rogue being capable of shanking a dude.

And so stealth also brings up trouble with regard to how hit points work. One of the primary benefits of sneaking up on an enemy combatant is the opportunity to quickly and quietly dispose of them. However, most enemies in D&D type games have more HP than a fighter can deal in damage in one round. This winds up being "role protectionism," for the rogue. Even if the monk, or ranger, or fighter, or paladin, etc. snuck up on the enemy, they would not be able to kill them quietly, or quickly, thus giving their little stealth operation a close to 0% chance of success (where success is taking the enemy dude out without alerting the other enemies).

But enough about the problems with stealth. How do we fix it?

Well, there are a number of things:

- Stop screwing characters in heavy armor. Seriously. Give them penalties to swimming, give them a hard time when they try to run more than 50 yards, but stop forcing them to auto-fail stealth checks with your gratuitous penalties. Armor is heavy, armor is expensive, and those two things together are more than enough to counterbalance the bonus to a character's defense. In reality, D&D-type games have been biased toward not wearing much armor for a long time. If you are regularly in hand-to-hand combat, wearing no armor is suicidal. All those leather-pants-wearing thieves out there who have complained enough to be allowed into front-line fighting are messing things up for their armor-bearing allies. Reality checks should be used very sparingly when it comes to fantasy games, but this is a spot where one is sorely needed.

- There are two types of "sneak attacks." Ones where you plan to eliminate your target, and ones where you plan to get in a solid first strike against a big evil guy like a dragon. Take that into consideration when you are stating up your NPCs and monsters. If the standard ol' city guards have 5d8+12 HP each, then only the rogue can ever hope to take them out with a surprise attack. Don't do that to your players. Let your player characters outrun the rest of humanity in terms of HP and bonuses and such as they level-up. That way, a normal city guardsman always has roughly 1-8 HP, and even the bard could kill him silently with a good stab in the back. If you were hoping for the city guard to put up a good fight against your magically equipped and time-tested PCs, you are designing your encounters wrong. Simple as that.

- If a PC critically fails a stealth check, they should be seen, no question. However, a regular fail on a stealth check should be interpreted more loosely as "a complication is added to the scenario." The castle guards stop to chat, and the careful timing you did of their rounds is now totally useless. A new NPC shows up to speak to the guard, or give him some food, or something else. A third party, like a wild animal or a beggar or something, shows up and draws attention in a direction you didn't want it drawn. The dog smells you and starts to bark from his cage, but the guards are just telling it to shut-up for now. This way, when the party rolls stealth all together, there are three possible outcomes: everyone succeeds and no complications arise, some people fail and complications arise, everyone fails (or at least one critically fails) and the PCs are discovered before their plan can occur. Now, the fighter and cleric can come along just like everyone else, but each additional person is another chance for a crit-fail to show up. Bigger party = harder to go unnoticed = perfectly reasonable to me.

- Be real about how aware the enemy really is. A small camp of orcs that is feasting and wrestling are essentially unaware of their surroundings unless they have posted a lookout (which should not always be the case, unless its wartime or something). Assuming there is no lookout, the PCs should be able to sneak around their camp (in the trees) without rolling anything. If they want to foot-pad into the camp, enter tents, steal food or gold, etc., then stealth checks are needed to see how well that goes, since a stray orc could easily befall them as they reach into the chests of treasure in the middle of the camp.

- Allow the players to solve the problem without rolling. If a rock thrown in the opposite direction of the entrance can draw the lookout away from his position long enough for the party to slip inside, then the party shouldn't need to roll stealth at all so long as they figured that out and did it. An invisibility spell + slow walking should allow a character to move through an open doorway without a problem, even with a guard a few feet away. Maybe a dexterity check might be needed if someone was to almost bump into them, but you get the drift.

Those are my best pieces of advice. If you have any other tips, or you've got the ultra-genius way of resolving stealth that I could never have conceived in a million years, please leave them in the comments. Pretty please?

Friday, April 8, 2016

Stories Better Told In-Game

I took the cleric and paladin classes out of my game because I felt that a character turning toward a religion was something that should happen during play. That moment that a warrior defends a temple and holy light shines down on them and they receive Pelor's blessing is too good to be passed up as mere "backstory." That's the meat and potatoes right there, not the appetizer!

A mortally wounded adventurer is carried into the hut of an old hermit woman, and as she prays over him, he sees a vision of Elhonna calling to him, telling him she needs him to spread her teachings. It's his destiny, which if not achieved, would yield terrible consequences. Boom, cleric (or missionary) origin. It has a sense of urgency and reality, rather than the distant and ephemeral relationship most cleric class members have with their deities.

This game decision was extremely freeing, because now religion didn't have to be part of the campaign if I didn't want it to be. Sure, characters could be religious, but unless I chose so, no divine powers (and thus near-direct deity involvement) would be required. Pantheons take a long time to make, man. Sometimes I just want murder-hobos fighting dragons in a godless hell-hole, but as soon as any divine class is allowed, there is an entirely new dimension to my world that I need to fill out, whether it will be used a lot or hardly ever.

Not to mention, NPC members of religions also got toned WAY down, so that they are nearly all mundane people with regular reasons for being religious, rather than magically gifted healers who can be the deus in your deus ex machina plot problem. AND a great corollary to this is: magic healing is much rarer, therefore the game feels more dangerous. May not be your thing, but it is so my thing.

This train of thought led me to arcane magic-users, M-Us, or "moos" for short. A moo is basically in the same boat as a cleric or paladin: they have some supernatural ability that everyone wants to know more about, but the narrative drive it creates is crippled by the game always beginning en media res of their development. A moo's first experience with magic is a defining and contextualizing moment of unprecedented importance in the story, but when it is resigned to the backstory, it matters not at all.

So, you can take moos out too, and make magic exactly like religion: you get it during play, if at all. Again, the freedom this offers is immeasurable. Now, if I don't want to incorporate pact magic and patrons in my game, I don't have to worry about a player choosing the warlock class. It also means magic (and religion) can be totally mysterious and not balanced, because it's all in-game development. It puts the risk-reward balance in player character choices, rather than character creation. No need for spell slots, no need for domains and specialization rules. Just cause and effect story.

Each spell or magical power is its own rule module with its own limits and costs and risks. If you want a bigger/better/cooler/flashier version of what you have, you can't just kill stuff until you level-up, you have to go out in search of the better version and learn how to do that. But be warned, it may have costs you are not willing to pay, or be on the other side of a challenge you are not ready to face.

Not having any set rules for how magic functions allows you to try different things for each moo, like magic atrophy, crude magic, modified vancian magic, wizard garment restrictions, a panoply, i.e. collection of magic foci, or the spell components you've been ignoring your whole life.... And so much more!

But wait! Won't these magic systems spin wildly out of control? Won't my moos either become gods among men, or slump over and give up because the costs of magic are too high and not balanced with the real classes?

It's all in how well you DM, of course. But rest assured, your moo isn't just a moo, he is also a warrior, or a dwarf, or a scoundrel, or some other mundane/race class first. Not all D&D characters live beyond their first couple adventures, and not all moos ever get to cast fireball before blowing themselves to smithereens in a magical mishap. All game systems have edge cases that screw things up. You deal with them as they come along. But at least with in-game magic only, your players (and you, to some extent) get the excitement and mystery of magic back in your campaign.

Players now have to actually choose whether gaining magical power is worth the risk. Parties now have to gather information on their sorcerous enemies before charging in, or risk death by unanticipated magic abilities. Playing a moo well now requires learning and exploring above all else, and especially above choosing the best spells at each level.

This fantasy RPG hobby of ours is about three things. First is being with friends, and what system you play should have no effect on that. Second is exploration of a magical world. If gaining magic is part of exploring, rather than part of the rulebook, then that's just more exploring to do. Win-win. Third, tabletop is about problem solving in a more dynamic and complex environment than any video game or board game can model. If you make magic a problem to be solved, and a challenge to be overcome, rather than something characters are just handed from the get-go, then you have all the more material to work with as a DM.

Until next time.

A mortally wounded adventurer is carried into the hut of an old hermit woman, and as she prays over him, he sees a vision of Elhonna calling to him, telling him she needs him to spread her teachings. It's his destiny, which if not achieved, would yield terrible consequences. Boom, cleric (or missionary) origin. It has a sense of urgency and reality, rather than the distant and ephemeral relationship most cleric class members have with their deities.

This game decision was extremely freeing, because now religion didn't have to be part of the campaign if I didn't want it to be. Sure, characters could be religious, but unless I chose so, no divine powers (and thus near-direct deity involvement) would be required. Pantheons take a long time to make, man. Sometimes I just want murder-hobos fighting dragons in a godless hell-hole, but as soon as any divine class is allowed, there is an entirely new dimension to my world that I need to fill out, whether it will be used a lot or hardly ever.

Not to mention, NPC members of religions also got toned WAY down, so that they are nearly all mundane people with regular reasons for being religious, rather than magically gifted healers who can be the deus in your deus ex machina plot problem. AND a great corollary to this is: magic healing is much rarer, therefore the game feels more dangerous. May not be your thing, but it is so my thing.

This train of thought led me to arcane magic-users, M-Us, or "moos" for short. A moo is basically in the same boat as a cleric or paladin: they have some supernatural ability that everyone wants to know more about, but the narrative drive it creates is crippled by the game always beginning en media res of their development. A moo's first experience with magic is a defining and contextualizing moment of unprecedented importance in the story, but when it is resigned to the backstory, it matters not at all.

So, you can take moos out too, and make magic exactly like religion: you get it during play, if at all. Again, the freedom this offers is immeasurable. Now, if I don't want to incorporate pact magic and patrons in my game, I don't have to worry about a player choosing the warlock class. It also means magic (and religion) can be totally mysterious and not balanced, because it's all in-game development. It puts the risk-reward balance in player character choices, rather than character creation. No need for spell slots, no need for domains and specialization rules. Just cause and effect story.

Each spell or magical power is its own rule module with its own limits and costs and risks. If you want a bigger/better/cooler/flashier version of what you have, you can't just kill stuff until you level-up, you have to go out in search of the better version and learn how to do that. But be warned, it may have costs you are not willing to pay, or be on the other side of a challenge you are not ready to face.

Not having any set rules for how magic functions allows you to try different things for each moo, like magic atrophy, crude magic, modified vancian magic, wizard garment restrictions, a panoply, i.e. collection of magic foci, or the spell components you've been ignoring your whole life.... And so much more!

But wait! Won't these magic systems spin wildly out of control? Won't my moos either become gods among men, or slump over and give up because the costs of magic are too high and not balanced with the real classes?

It's all in how well you DM, of course. But rest assured, your moo isn't just a moo, he is also a warrior, or a dwarf, or a scoundrel, or some other mundane/race class first. Not all D&D characters live beyond their first couple adventures, and not all moos ever get to cast fireball before blowing themselves to smithereens in a magical mishap. All game systems have edge cases that screw things up. You deal with them as they come along. But at least with in-game magic only, your players (and you, to some extent) get the excitement and mystery of magic back in your campaign.

Players now have to actually choose whether gaining magical power is worth the risk. Parties now have to gather information on their sorcerous enemies before charging in, or risk death by unanticipated magic abilities. Playing a moo well now requires learning and exploring above all else, and especially above choosing the best spells at each level.

This fantasy RPG hobby of ours is about three things. First is being with friends, and what system you play should have no effect on that. Second is exploration of a magical world. If gaining magic is part of exploring, rather than part of the rulebook, then that's just more exploring to do. Win-win. Third, tabletop is about problem solving in a more dynamic and complex environment than any video game or board game can model. If you make magic a problem to be solved, and a challenge to be overcome, rather than something characters are just handed from the get-go, then you have all the more material to work with as a DM.

Until next time.

Thursday, March 17, 2016

Bounded Numbers Fix Boring Players

Nearly every person I've ever played D&D with is my close friend, and I love each of them very, very much. Having said that, I absolve myself of the hard feelings that might come with saying this: some of them are bad players.

By bad, I don't mean "they roll low all the time," a la Wil Wheaton, nor do I mean "they don't have an expert grasp of the rules," and in fact, those of my friends who understand the rules the least, and roll the lowest (on average) are often the best players. Rather, I mean they make uninteresting choices at nearly every opportunity, and count on the scaling within the game to make their character more effective, rather than counting on their own problem solving instincts.

There are several things that exacerbate this problem, such as lists, overly complex combat rules, and cookie-cutter encounters. Another mechanic that pours salt in the wound is unbounded numbers.

When bounded accuracy was announced as a major feature of D&D 5, I was very excited. I thought that bounded to-hit numbers, combined with a simple advantage/disadvantage mechanic, would result in a huge increase in player creativity at the table, particularly in combat.

But, I was wrong.

Things stayed the same, because damage continued to scale with level like it always did, and even worse, magic item bonuses are not calculated into the monster challenge rating math anymore, so most creatures will likely have less Hit Points than they should for the level of characters you throw them at.

That means monsters aren't all that hard to kill for characters of the appropriate level...

Which means just attacking and standing still is likely to win you the fight, all the math considered.

That's not my kind of game.

In my kind of game, players will likely die if they simply choose to attack a creature head-on, after level 3 or so. Goblins and dire rats and other such level 1 and 2 fodder shouldn't be a serious problem unless a character makes a bad mistake or gets totally surrounded. That's what intro levels are for: establishing a feel for the world, the game, and the ground rules of life-and-death. But once you enter larger monster territory, even just burly things like bugbears, the fear of god should be in the PCs if they don't have a plan that involves something more effective than "I swing my axe."

This means using the environment, taking creatures by surprise, enlisting further help from some townsfolk or mercenaries, or counting on a specific magic item to save your ass (if you're desperate).

A system can help you create combat that requires more creativity from your players, it just needs to be built keeping one thing in mind: characters should likely die in a fair fight against higher level creatures.

That's how you advance in a tabletop RPG: the character improves only enough to justify making the low level and high level monsters mechanically different, AND the PLAYERS get better at thinking about and approaching combat, and further analyze (in-game) how to increase their chances of survival.

A fighter character's sword skills should only become marginally more deadly through his tenure as an adventurer. But his combat skills should become MUCH more deadly, and this is only truly manifest via player improvement, not better numbers on a character sheet.

______________________________________________________

What you may notice is that this approach to designing a system would make random encounters particularly dangerous. While the discussion about the merits of random encounters is a whole different conversation, I will put this forward: good players should be able to get some kind of upper hand no matter what you throw at them, nor when. This doesn't mean they will win, or even survive, but it means that they will find something to work with.

By bad, I don't mean "they roll low all the time," a la Wil Wheaton, nor do I mean "they don't have an expert grasp of the rules," and in fact, those of my friends who understand the rules the least, and roll the lowest (on average) are often the best players. Rather, I mean they make uninteresting choices at nearly every opportunity, and count on the scaling within the game to make their character more effective, rather than counting on their own problem solving instincts.

There are several things that exacerbate this problem, such as lists, overly complex combat rules, and cookie-cutter encounters. Another mechanic that pours salt in the wound is unbounded numbers.

When bounded accuracy was announced as a major feature of D&D 5, I was very excited. I thought that bounded to-hit numbers, combined with a simple advantage/disadvantage mechanic, would result in a huge increase in player creativity at the table, particularly in combat.

But, I was wrong.

Things stayed the same, because damage continued to scale with level like it always did, and even worse, magic item bonuses are not calculated into the monster challenge rating math anymore, so most creatures will likely have less Hit Points than they should for the level of characters you throw them at.

That means monsters aren't all that hard to kill for characters of the appropriate level...

Which means just attacking and standing still is likely to win you the fight, all the math considered.

That's not my kind of game.

In my kind of game, players will likely die if they simply choose to attack a creature head-on, after level 3 or so. Goblins and dire rats and other such level 1 and 2 fodder shouldn't be a serious problem unless a character makes a bad mistake or gets totally surrounded. That's what intro levels are for: establishing a feel for the world, the game, and the ground rules of life-and-death. But once you enter larger monster territory, even just burly things like bugbears, the fear of god should be in the PCs if they don't have a plan that involves something more effective than "I swing my axe."

This means using the environment, taking creatures by surprise, enlisting further help from some townsfolk or mercenaries, or counting on a specific magic item to save your ass (if you're desperate).

A system can help you create combat that requires more creativity from your players, it just needs to be built keeping one thing in mind: characters should likely die in a fair fight against higher level creatures.

That's how you advance in a tabletop RPG: the character improves only enough to justify making the low level and high level monsters mechanically different, AND the PLAYERS get better at thinking about and approaching combat, and further analyze (in-game) how to increase their chances of survival.

A fighter character's sword skills should only become marginally more deadly through his tenure as an adventurer. But his combat skills should become MUCH more deadly, and this is only truly manifest via player improvement, not better numbers on a character sheet.

______________________________________________________

What you may notice is that this approach to designing a system would make random encounters particularly dangerous. While the discussion about the merits of random encounters is a whole different conversation, I will put this forward: good players should be able to get some kind of upper hand no matter what you throw at them, nor when. This doesn't mean they will win, or even survive, but it means that they will find something to work with.

Monday, February 15, 2016

Fantasy Archetypes as Chronology, and the Expanding Magician

There is some great blog literature about the cleric as a misfit in the fantasy world, and I suggest that you all read it if you get the chance. A good place to start is Delta's discussions of the cleric and how it bothered him throughout the years (scroll down to the bottom of the post).

This excommunication of the cleric would then leave us with three archetypes: the warrior, the scoundrel, and the magician. Three is a nice number. It lends itself well to overthinking and false analogies. The following may or may not be one of those.

Warrior, Scoundrel, Magician = Present, Future, and Past

The warrior is living for the glory, the thrill, the power. But the warrior's glory does not come after the fight, it comes during the fight, as he (or she) is flaying the dragon, beheading the minotaur, or stabbing the orc general. His strength and potency comes from what he can do right now. A general without an army to command right now is not really a general.

Warriors are typically depicted as men, in the real world, and even in fantasy. There are a host of stereotypes that explain this, but perhaps one of the least examined is the correlation between the male brain and mental focus: paying attention deeply to one thing is emphasized, but planning ahead and multi-tasking are underutilized.

I would argue that the warrior archetype is inherently uninterested in planning ahead and multi-tasking. It doesn't mean a warrior can't plan, or multi-task. But there is something about the warrior culture and warrior mindset that implies addressing problems as they arise with whatever strengths and strategies become available in real time.

In game terms, this means the warrior excels after combat starts. Once each combatant must begin making decisions and acting on them, the warrior is most in control. This means being reactionary. But very effectively so. "He does A, so I respond with B. She does C, so I respond with D." That kind of cause-effect reality means warriors are inherently focused on the present in order to be effective.

The Scoundrel, on the other hand, is most effective when they can predict what challenges lay before them. This can be boiled down to the mind-numbing mundanity of "I search for traps," but it also exists at all the other levels of interesting play. Cat burglars and art thieves stake out their targets to better predict what they will be up against. They set up road-side robberies as chests of gold are being transported from the royal coffers.

Even combat oriented scoundrels are focused on setting up a future opportunity to strike for maximum effect.

Scoundrels are the ones that walk away with the gold, avoid consequences, disappear into anonymity, etc. That doesn't happen on the fly, it happens because these archetypical characters are constantly planning. "If he does X, I will do Y. But, if he does W, I will do Z." A scoundrel's mind must always be playing with possible future worlds, and planning not just the next move, but the next three moves like a chess grandmaster.

The magician exists in the past. A magician's influence depends on what archaic secrets of the old world they can master, and what incredible shifts of reality they have accomplished. The magician is potent not based on how they can react to what their enemies are doing, nor how well they have planned to deal with their opponents' strategy. A magician is powerful based solely on what they are independently capable of. If you can incinerate a man at the flick of a wand, the most important part of your development as a magician was not the moment of incineration, nor the plan you concocted to find and incinerate that person. It was the moment you figured out how to incinerate someone. The sheer unpredictability of your powers is, in itself, dangerous.

"I have amassed this power," the magician says. "Try and stop me if you wish."

This makes the magician sound like an evil archetype. And it sure as hell works for evil characters. But it can also be a force for good. Unless you live in a world that has entirely collapsed to evil, then evil must have been defeated or staunched in some way before, but you can only find out what those methods were by looking to the past.

_____________________________________________________________

This tripartite comparison creates its own rock-paper-scissors relationship as well. Warrior is reaction, magician is unpredictability, and scoundrel is prediction. The warrior beats the magician, because the only way to beat something that's unpredictable is to react efficiently and effectively at a moment's notice. The magician beats the scoundrel, because if the scoundrel cannot predict their opponent's capabilities, their advantage is lost. And lastly, the scoundrel beats the warrior, because it is trivial to predict something that works on a basic cause-effect, action-reaction formula, and it is therefore easy to counter.

_____________________________________________________________

Yet another insight from this comparison is what it has to say about the magician and "game balance." I'm not talking about balance in the sense of "the magician shouldn't deal more damage than the warrior" or "shouldn't roll higher stealth checks than the scoundrel." Rather, I'm talking about giving your players and their characters roughly equal time to shine in any given game. Warriors are best at reacting to sudden events, and scoundrels are best at planning how to circumvent the better part of the challenges they can predict. The magician should be pure, raw magical effect.

But if you let the magician prepare too accordingly for the challenges they will face, then it begins to overshadow the scoundrel. Who needs to sneak around the frost giants and set their fortress on fire if the magician has a dozen fire spells prepared?

By the same token, if you allow spells to become too utilitarian, and give the magician too many of them, then they start to overshadow the warrior. Oh, the demon has summoned two fire beasts? Well, my wall of iron will keep them at bay. Now the demon is trying to disintegrate my wall? I cast arcane transference and absorb his spell, then use the spell slot I gain from that to cast sonic boom against the crystal golems, which is an auto-critical.

See what I mean? Old school magicians, with their tiny spell lists and laughable number of spells per day were like a shotgun: effective when used for its intended purpose, somewhat effective if used for a well-thought-out improvised purpose, and disastrous if used for anything else. Sure, you can shoot an enemy with a shotgun, and you can even blow open a locked door with a shotgun, but you can't put out a house fire with a shotgun, and you can't create an anti-venom with a shot gun. During those times, other characters get to shine.

But the trend in magicians has been to transform them into a Swiss-army knife/multi-tool/Skeleton key archetype, where they can steal the spotlight entirely, so long as they do their research and prepare the right spells. Not only is this unfair to the players who want to make characters that aren't magicians, but it also is opposite the original feel of the magician. Archaic and arcane secrets aren't a dime a dozen. In the LOTR movies, Gandalf was away for over a year doing research and hunting gollum just to learn about the history and tell-tale signs of the One Ring.

In the books, that quest takes him exactly seventeen years. I don't think that much time should be necessary to discover some arcane secrets, but you get the drift.