That is, not inspired by Tolkien or Peter Jackson.

Because, let's be honest, they have no personalities or characteristics of their own.

There are only three women with actual dialogue in the four main books about Middle Earth, and two of them fall in love with the same guy (barf, have some individual development please). And the third (Galadriel) is so powerful and otherworldly as to be beyond gender entirely. If Tolkien didn't want the leader of the Elves to be indescribably beautiful, he would have made her a man.

This is the problem with Dwarves, as well as countless other races in your standard fantasy games: they could easily be supplanted. In this case, by eccentric humans. If that is true, I say make them humans, or make them more interesting.

Dwarves are just short humans with Scottish accents that like gold. Hell, even living underground is not enough to make them interesting. Think about it: a culture of humans that live underground would interest your players a LOT more than the standard Dwarf civilization. And of course they would value gold and rare earths a lot, that is one of the only natural resources available underground.

Here's how I would do Dwarves:

-Dwarves are deathly afraid of the surface world. Dwarves that go above ground are their race's equivalent to cosmonauts, and have to physiologically adjust over time, too.

-Dwarves cannot swim. They sink like rocks. They can't even be trained to swim. It's just physics.

-Dwarves will go to war with almost anyone to acquire rich mineral veins. Usually, they try to sneak underground and mine the jewels and metals without being noticed, but if they have to fight, or if the city/town above collapses, they usually don't give a fart. (P.S. Some dwarven activists protest this theft of minerals). (P.P.S I'm pretty sure I got this from another blog, but I can't find the link for the life of me.)

-Dwarves are agnostic. No sky = no great and mysterious lights = no creation myths. HOWEVER, the dwarven cosmonauts do worship a long-dead mortal being who trained their first group in the ways of surface living.

-Dwarves eat root vegetables, fungi, and insects only. Not a lot of deer to hunt underground. Not many apple trees either. Dwarven alcohol is made from fermenting these three food groups. No grain-alcohols.

-Dwarves don't smith. [GASP!] Because they don't like digging vents to the surface world, and lighting fires/forges underground is a sure-fire (pun intended) way to die of smoke inhalation. Instead, dwarves have developed a magic system based off of magnetism that allows them to very effectively bind cold-smithed metals together. They make mostly art, architecture, and digging/smithing tools with this magic.

-Native dwarven weapons are stone: they wouldn't dare waste their metals on things made to smash and break. They also wear no armor, because they lack the resources to make suitable light protection (primarily leather).

-Dwarves don't bathe while underground. For them, the feeling of a light layer of dust and dirt on their skin is ideal. The cosmonauts do bathe, but they sand/dirt bathe. Mostly to get the weird green plant matter and occasional moisture off their skin. Gross.

-I see no reason why dwarves should live for many hundreds of years. I'd stick their expected age range between 175 and 200 years.

That's it for today, I'll do Eladrin/High Elves and Wood Elves tomorrow.

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Help! My Players Don't Know What To Do

So your players aren't biting at those hooks you set.

Or perhaps they are biting...just too easily. They don't bother to do any oblique thinking. They willingly railroad themselves into a plot. They wait for you (the DM) to hand deliver them a quest, but you want them to explore with some self-direction.

Your problem is that your world has no detail.

Dedicated players cannot help but be intrigued by world details. But the details that DMs usually put in don't spark action, or generate questions.

For example: "You walk into the next room in the dungeon, a forty foot by thirty foot by ten foot chamber with more dark stone walls and carved floors. It isn't as musty as the previous rooms. There is a wooden table with matching chair in the center of the room, a goblin body is sprawled across the table with a roughly crafted dagger sticking out of its back. There are six silver pieces in the goblin's pockets. On the other side of the room is another wooden door."

You can probably pictures that room well, and you would be confidently interacting with it if you were a player. But you wouldn't get anything from it except "you should probably continue into the next room, and there are other things alive down here, if you didn't already know that."

But that isn't enough. Where are the things that the players will hold onto when they leave the dungeon? Where are the tiny hooks into future adventure?

The answer is: on a half dozen random tables that you need to generate now. Like, right now. d100s.

Table 1: Random names. Each entry should have one humanoid name and one monstrous one.

Table 2: Motives. A big list of things this creature or NPC could be doing/involved with.

Table 3: LOOT. A list of stuff that enemy or NPC might have on them.

Table 4: Details. Roll with the LOOT table to get unique treasure every time. Ex: "Has an elvish rune on it."

Table 5: Dungeon Motifs. Yeah, it's dwarvish. But maybe it was built by dwarves that had giants as slaves...

Table 6: PLOT TWIST. A list of random things that an NPC or monster could do to mix things up.

The point of these tables is that, without them, the DM rarely fills in these blanks, even though they would always be filled in if this were real. That dagger in the goblin's back will just be a shitty dagger if not for these tables. But a shitty dagger with an elvish inscriptions? (Hell, make a random inscription table...) Now that's interesting and worth questing about.

Every time you, as the DM, put a goblin in the dungeon that doesn't have any reason to be there other than as an encounter for the PCs, you've wasted time and energy. But giving each goblin a story while you prep for the session would be ridiculous. That's what the tables are for. If the PCs are in too much of a rush to loot and examine that dead goblin, then that's that. Other things are more interesting right now, and you can leave that goblin as "just a goblin." But start encouraging your PCs to explore the details.

You'd be surprised at the level of storytelling that emerges from stupid details.

Think about it. Those six silver pieces in the goblins pocket? Why are they there? Money doesn't just appear in people's pockets (unfortunately). That goblin did something to earn those silver pieces. Maybe he found them on the ground while heading back to the dungeon after being kicked out of his goblin group. Maybe he killed someone for pay. Maybe he cheated in a card game, and his opponents let him keep the silver, but put a blade between his shoulder blades as a parting gift. That could be another table: How did this guy get this money, d100. You get the drift.

Just be ready to fill in the details when the PCs want you to, but don't do random details off the top of your head. Put them together earlier, and craft them to be sure every single detail is a stepping stone for more adventure.

Or perhaps they are biting...just too easily. They don't bother to do any oblique thinking. They willingly railroad themselves into a plot. They wait for you (the DM) to hand deliver them a quest, but you want them to explore with some self-direction.

Your problem is that your world has no detail.

Dedicated players cannot help but be intrigued by world details. But the details that DMs usually put in don't spark action, or generate questions.

For example: "You walk into the next room in the dungeon, a forty foot by thirty foot by ten foot chamber with more dark stone walls and carved floors. It isn't as musty as the previous rooms. There is a wooden table with matching chair in the center of the room, a goblin body is sprawled across the table with a roughly crafted dagger sticking out of its back. There are six silver pieces in the goblin's pockets. On the other side of the room is another wooden door."

You can probably pictures that room well, and you would be confidently interacting with it if you were a player. But you wouldn't get anything from it except "you should probably continue into the next room, and there are other things alive down here, if you didn't already know that."

But that isn't enough. Where are the things that the players will hold onto when they leave the dungeon? Where are the tiny hooks into future adventure?

The answer is: on a half dozen random tables that you need to generate now. Like, right now. d100s.

Table 1: Random names. Each entry should have one humanoid name and one monstrous one.

Table 2: Motives. A big list of things this creature or NPC could be doing/involved with.

Table 3: LOOT. A list of stuff that enemy or NPC might have on them.

Table 4: Details. Roll with the LOOT table to get unique treasure every time. Ex: "Has an elvish rune on it."

Table 5: Dungeon Motifs. Yeah, it's dwarvish. But maybe it was built by dwarves that had giants as slaves...

Table 6: PLOT TWIST. A list of random things that an NPC or monster could do to mix things up.

The point of these tables is that, without them, the DM rarely fills in these blanks, even though they would always be filled in if this were real. That dagger in the goblin's back will just be a shitty dagger if not for these tables. But a shitty dagger with an elvish inscriptions? (Hell, make a random inscription table...) Now that's interesting and worth questing about.

Every time you, as the DM, put a goblin in the dungeon that doesn't have any reason to be there other than as an encounter for the PCs, you've wasted time and energy. But giving each goblin a story while you prep for the session would be ridiculous. That's what the tables are for. If the PCs are in too much of a rush to loot and examine that dead goblin, then that's that. Other things are more interesting right now, and you can leave that goblin as "just a goblin." But start encouraging your PCs to explore the details.

You'd be surprised at the level of storytelling that emerges from stupid details.

Think about it. Those six silver pieces in the goblins pocket? Why are they there? Money doesn't just appear in people's pockets (unfortunately). That goblin did something to earn those silver pieces. Maybe he found them on the ground while heading back to the dungeon after being kicked out of his goblin group. Maybe he killed someone for pay. Maybe he cheated in a card game, and his opponents let him keep the silver, but put a blade between his shoulder blades as a parting gift. That could be another table: How did this guy get this money, d100. You get the drift.

Just be ready to fill in the details when the PCs want you to, but don't do random details off the top of your head. Put them together earlier, and craft them to be sure every single detail is a stepping stone for more adventure.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

2 Things to Use in your Campaign

1: Sea Monsters

For the love of gods, why aren't sea serpents used more in games like D&D? I don't own the 5e Monster Manual, but I am pretty sure there is roughly one kind of giant sea monster: the kraken.

Don't get me wrong, I love me some krakens. I've used them. I've had them attack ships. I've had them attack subterranean Aboleth cadres in Pacific Rim-type cave-lake encounters. Super fun.

But there is SO MUCH MORE sea monster mythology out there to be used. Hell, you can throw anything underwater and make it cooler.

How about aquatic hobgoblins? No, not sahuagin (or whatever they are called). As soon as you put a fish face on something, it looks stupid. Big dumb eyes and wide toothless mouths. That is not scary. Why not more aquatic mammals or reptiles that need to breath air, but not very often.

Like a crocodile. Sweet mother of Thor crocodiles are scary. Stealth killers that get you at the watering hole?

Terrifying.

Also: water. No need to add all those ridiculous terrain changes and traps and whatnot. Deep water is scary enough as is.

2: Battle Formations

Smart enemies fight in formation. Maybe not a straight line, or a tortuga, or whatever that roman thing was with all the shields and spears and such, but they know where they are supposed to be to make things as bad as possible for the PCs.

This means you can't just sprinkle the hobgoblins on the random forest map and expect it to end up like a real fight. And I don't mean "real" as in "like the real world," I mean real as in "dramatic and requiring strategy."

Let's see some regrouping and battle chants and (for the bigger battles) war drums and horns and such. Opportunity attacks make this needlessly difficult, which is why I hate them.

But at least consider allowing the monsters or PCs to pull back and reestablish positions on higher ground or better terms.

For the love of gods, why aren't sea serpents used more in games like D&D? I don't own the 5e Monster Manual, but I am pretty sure there is roughly one kind of giant sea monster: the kraken.

Don't get me wrong, I love me some krakens. I've used them. I've had them attack ships. I've had them attack subterranean Aboleth cadres in Pacific Rim-type cave-lake encounters. Super fun.

But there is SO MUCH MORE sea monster mythology out there to be used. Hell, you can throw anything underwater and make it cooler.

How about aquatic hobgoblins? No, not sahuagin (or whatever they are called). As soon as you put a fish face on something, it looks stupid. Big dumb eyes and wide toothless mouths. That is not scary. Why not more aquatic mammals or reptiles that need to breath air, but not very often.

Like a crocodile. Sweet mother of Thor crocodiles are scary. Stealth killers that get you at the watering hole?

Terrifying.

Also: water. No need to add all those ridiculous terrain changes and traps and whatnot. Deep water is scary enough as is.

2: Battle Formations

Smart enemies fight in formation. Maybe not a straight line, or a tortuga, or whatever that roman thing was with all the shields and spears and such, but they know where they are supposed to be to make things as bad as possible for the PCs.

This means you can't just sprinkle the hobgoblins on the random forest map and expect it to end up like a real fight. And I don't mean "real" as in "like the real world," I mean real as in "dramatic and requiring strategy."

Let's see some regrouping and battle chants and (for the bigger battles) war drums and horns and such. Opportunity attacks make this needlessly difficult, which is why I hate them.

But at least consider allowing the monsters or PCs to pull back and reestablish positions on higher ground or better terms.

Saturday, February 7, 2015

Relative Level Instead of Objective Level

I have been drowning myself in design theory of late, and I think I came across a diamond in the rough. I guess you will have to be the judge of that.

Fact: Many many P&P RPG players enjoy character advancement. "Leveling up," if you will. Being better at challenges previously encountered, after enough training/time/exposure/experience points. They want to feel the progression. It allows them to speak confidently about what their character can do when roleplaying.

Fact: Leveling up is the #1 cause of very annoying number inflation in P&P RPGs. Dragons need high attack bonuses and armor class rating because they are fighting high level PCs, whereas goblins can have nice, small, understandable numbers because they fight low level PCs who also have nice, small, understandable stats and bonuses. If this were not the case, fighting a goblin and fighting a dragon would be equally challenging. That doesn't make sense.

(Potentially new and valuable) Fact: The objective stats of the dragons and goblins don't matter. What matters is only the relative stats of the goblins and the PCs, or the dragons and the PCs. Is the dragon a higher level than the PCs? Are the goblins a higher level than the PCs? Lower?

How to apply the fact:

So when the level 1 PCs first meet the goblins, who are also level 1, there isn't any extra math to do.

Fact: Many many P&P RPG players enjoy character advancement. "Leveling up," if you will. Being better at challenges previously encountered, after enough training/time/exposure/experience points. They want to feel the progression. It allows them to speak confidently about what their character can do when roleplaying.

Fact: Leveling up is the #1 cause of very annoying number inflation in P&P RPGs. Dragons need high attack bonuses and armor class rating because they are fighting high level PCs, whereas goblins can have nice, small, understandable numbers because they fight low level PCs who also have nice, small, understandable stats and bonuses. If this were not the case, fighting a goblin and fighting a dragon would be equally challenging. That doesn't make sense.

(Potentially new and valuable) Fact: The objective stats of the dragons and goblins don't matter. What matters is only the relative stats of the goblins and the PCs, or the dragons and the PCs. Is the dragon a higher level than the PCs? Are the goblins a higher level than the PCs? Lower?

How to apply the fact:

- Player characters record their level simply as a number from 1 to (whatever you want as a cap). Leveling up can work however you want it to.

- When the PCs get in a fight with a monster, the higher level combatant(s) get a bonus to their rolls, and the lower level combatant(s) get a penalty to their rolls. This can be a static and constant +/- 1, or it could scale with the difference in level. Your choice.

- Equal levels across the board means no adjustments.

- You don't have to adjust most other stats for level. Ever.

So when the level 1 PCs first meet the goblins, who are also level 1, there isn't any extra math to do.

Then, after the goblins, the level 1 PCs run into an owlbear, level 3. Uh oh, the owlbear gets a +1 to its attack rolls, saves, etc. etc. AND, the PCs get -1 to attack rolls, saves, etc. etc. It proves too hard and the PCs flee successfully.

A few sessions later, the same group of PCs, now level 4, go find this owlbear to get revenge. Well, now the PCs benefit from a +1 to rolls, and the owlbear suffers the -1.

That net change of +/- 2 could mean the difference between expecting success and being doomed to defeat, depending on your system's math. If it doesn't, make the swing big enough to cause the difference...or make the math of your system more bounded.

So player characters do get better, but not because of a big number on their sheet. They get better because they keep adding more and more monsters to the category that grants them bonuses while fighting.

Thoughts?

Thursday, February 5, 2015

He had a Gaping Vortex in his Chest

Enter O'Malley. An undead dwarven justicar with an eldritch vortex of infinite pain taking up most of his torso.

He was an NPC that I'll never forget. And he is the result of an encounter that was too high level for the PCs.

This reaches back to the infamous Nick's Campaign (3.5 D&D) that I mentioned in my introduction page. I was a player, and I was a monk, and I hated it. But Nick was such a fantastic DM, and my friends were so swept up in the awesomeness of the sessions, that I couldn't help but get swept up too. Ah, nostalgia.

See, Nick had done something that many, many DMs refuse to do: he posed us, a group of rather inexperienced players, with an encounter that was way, WAY out of our league. He let us prepare for it. He let us think that, with the (then living and quite friendly) Justicar and some townsfolk with pitchforks, we could handle it (what the actual encounter was I no longer remember).

We could not handle it. Not at all. We had to flee. And the worst part, we had to leave the Justicar behind.

To die.

To be raised from death.

And to be controlled by a terrible, horrible, evil wizard from Ravenloft named Ian Mcalister.

O'Malley returned a few sessions later, looking bad, but not so bad that we saw his as a threat. He walked right up to our wizard in a tavern an double crit on a surprise attack.

Bye-bye wizard head.

Ian Mcalister had sent O'Malley after us, to hunt us down and kill us with the very man who embodied our failures as a party. O'Malley was our past sins pulling the strings of our future fate.

We fought against O'Malley, his wizard overlord, and countless other abominations in a final-stand fort-defense battle. Our wizard (resurrected, though painfully), used some dark magic tome to cast Finger of Death on Ian Mcalister and save us all.

But O'Malley got away. No longer was he a puppet, but he still harbored a hate for us that could not be satisfied.

And we had sinned again. Our wizard had given in to the dark side to defeat evil, and this set in motion an entirely new course of events.

We were not heroes. We were survivors. We had abandoned people when it put us in too much danger. We had used arcane horrors to fight back the darkness. We had delayed and allowed the forces of evil to muster this far.

But such is war. Lord of the Rings may feature shining heroes without a bit of red in their ledgers, but we've all heard Lord of the Rings. It's over now. Good vs. Evil is no longer an interesting story when the lines are drawn so clearly.

Fantasy books and Fantasy RPGs have gone beyond fairytales and bedtime stories and become literature. They have become about people and their faults.

So give your players something to fail at. Give them situations with no easy answer. Give them hard choices. It shouldn't be a cheap shot, or contrived. It should be organic, and the guilt and regret should come from the players recognizing that their character took on a responsibility, and failed to live up to it.

We tried to save O'Malley's town. But we couldn't. We wanted to. We really did. But we misjudged our enemy. And Nick, the DM, let us do that. He let us walk into a death trap.

Sure, in the long run, fleeing meant losing a battle to win the war. It was for the greater good.

But the greater good should always have consequences in the now. That's why it is the greater good. Because it takes honest roleplaying and hard decisions to achieve it. If it were easy every time, or if the encounter was always winnable, then it wouldn't be a story about the greater good.

It would just be a story about regular ol' good. We have real life for that.

He was an NPC that I'll never forget. And he is the result of an encounter that was too high level for the PCs.

This reaches back to the infamous Nick's Campaign (3.5 D&D) that I mentioned in my introduction page. I was a player, and I was a monk, and I hated it. But Nick was such a fantastic DM, and my friends were so swept up in the awesomeness of the sessions, that I couldn't help but get swept up too. Ah, nostalgia.

See, Nick had done something that many, many DMs refuse to do: he posed us, a group of rather inexperienced players, with an encounter that was way, WAY out of our league. He let us prepare for it. He let us think that, with the (then living and quite friendly) Justicar and some townsfolk with pitchforks, we could handle it (what the actual encounter was I no longer remember).

We could not handle it. Not at all. We had to flee. And the worst part, we had to leave the Justicar behind.

To die.

To be raised from death.

And to be controlled by a terrible, horrible, evil wizard from Ravenloft named Ian Mcalister.

O'Malley returned a few sessions later, looking bad, but not so bad that we saw his as a threat. He walked right up to our wizard in a tavern an double crit on a surprise attack.

Bye-bye wizard head.

Ian Mcalister had sent O'Malley after us, to hunt us down and kill us with the very man who embodied our failures as a party. O'Malley was our past sins pulling the strings of our future fate.

We fought against O'Malley, his wizard overlord, and countless other abominations in a final-stand fort-defense battle. Our wizard (resurrected, though painfully), used some dark magic tome to cast Finger of Death on Ian Mcalister and save us all.

But O'Malley got away. No longer was he a puppet, but he still harbored a hate for us that could not be satisfied.

And we had sinned again. Our wizard had given in to the dark side to defeat evil, and this set in motion an entirely new course of events.

We were not heroes. We were survivors. We had abandoned people when it put us in too much danger. We had used arcane horrors to fight back the darkness. We had delayed and allowed the forces of evil to muster this far.

But such is war. Lord of the Rings may feature shining heroes without a bit of red in their ledgers, but we've all heard Lord of the Rings. It's over now. Good vs. Evil is no longer an interesting story when the lines are drawn so clearly.

Fantasy books and Fantasy RPGs have gone beyond fairytales and bedtime stories and become literature. They have become about people and their faults.

So give your players something to fail at. Give them situations with no easy answer. Give them hard choices. It shouldn't be a cheap shot, or contrived. It should be organic, and the guilt and regret should come from the players recognizing that their character took on a responsibility, and failed to live up to it.

We tried to save O'Malley's town. But we couldn't. We wanted to. We really did. But we misjudged our enemy. And Nick, the DM, let us do that. He let us walk into a death trap.

Sure, in the long run, fleeing meant losing a battle to win the war. It was for the greater good.

But the greater good should always have consequences in the now. That's why it is the greater good. Because it takes honest roleplaying and hard decisions to achieve it. If it were easy every time, or if the encounter was always winnable, then it wouldn't be a story about the greater good.

It would just be a story about regular ol' good. We have real life for that.

Monday, February 2, 2015

I LOVE LOW HIT POINTS

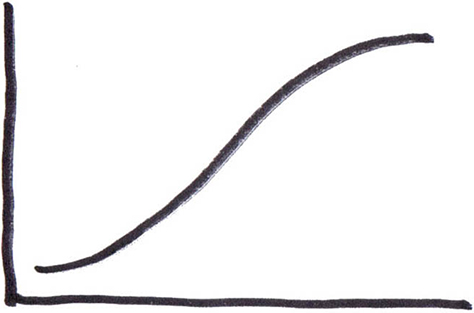

My ideal way to do HP is the old school way. Start with a good amount (two or three direct goblin attacks worth), then gain a d6 each level, but only up until a point. After that, it is a constant, small bonus for each level thereafter. It creates a diminishing returns effect (see Goblin Punch's System page for more on that), which looks a little like this:

That way the players feel like they are going somewhere early on, but they don't go so far that early threats become completely non-threatening. Also, this prevents later threats (i.e. monsters) from needing stats in the low quintillions to be a challenge for high level PCs.

Some people think you need a morale/energy/wind/fatigue AND guts/wounds/blood/constitution system to distinguish a character's actual wounds from mere shake-off-able battle wear.

Nope.

Low HP totals plus mild healing mechanics do that for you. You have 25 HP? You lose 15 HP in a fight? That's blood and guts, er, fatigue and wounds, er, whatever. You regain 4 HP after the fight with some small once-a-day self heal? Well, that 4 HP was the shake-off-able battle wear. No need to distinguish it when it happens.

But then the Paladin uses Lay on Hands? And you gained another 5 HP back? Great! That was guts. Or maybe wounds and morale, er, whatever. Doesn't matter.

The whole problem these dual-HP pool systems are trying to solve is that a barbarian with 289 HP doesn't feel half as ready to fight as one with 578 HP...because...well...he just doesn't. So they say, "Well, now the barbarian has 136 blood and 28 guts, so he's not tired, but he is pretty injured."

Personally, I think this is a terrible solution.

Our piddly human brains can't attach significance to numbers that high when it comes to bodily harm and battle fatigue. How many arrows have to be impaled in my fighter's back before he loses 100 Blood? 100 Guts? Hell if I know! How about if I had just 17 HP maximum? Well, now, probably three or four arrows would do ya (hey! just like Boromir!). Simple. Intuitive. Doesn't scare away the History majors at the table.

I don't care what your game's power-level is. I don't care if you are all playing superheroes who actively pick up entire city blocks and throw them at their enemies. The math behind a game does not, I repeat, DOES NOT have to scale with the strength of the characters and monsters if they were real.

The math of a game only ever has to scale with player understanding.

|

| (HP is the y-axis, Level is the x-axis) |

Some people think you need a morale/energy/wind/fatigue AND guts/wounds/blood/constitution system to distinguish a character's actual wounds from mere shake-off-able battle wear.

Nope.

Low HP totals plus mild healing mechanics do that for you. You have 25 HP? You lose 15 HP in a fight? That's blood and guts, er, fatigue and wounds, er, whatever. You regain 4 HP after the fight with some small once-a-day self heal? Well, that 4 HP was the shake-off-able battle wear. No need to distinguish it when it happens.

But then the Paladin uses Lay on Hands? And you gained another 5 HP back? Great! That was guts. Or maybe wounds and morale, er, whatever. Doesn't matter.

The whole problem these dual-HP pool systems are trying to solve is that a barbarian with 289 HP doesn't feel half as ready to fight as one with 578 HP...because...well...he just doesn't. So they say, "Well, now the barbarian has 136 blood and 28 guts, so he's not tired, but he is pretty injured."

Personally, I think this is a terrible solution.

Our piddly human brains can't attach significance to numbers that high when it comes to bodily harm and battle fatigue. How many arrows have to be impaled in my fighter's back before he loses 100 Blood? 100 Guts? Hell if I know! How about if I had just 17 HP maximum? Well, now, probably three or four arrows would do ya (hey! just like Boromir!). Simple. Intuitive. Doesn't scare away the History majors at the table.

I don't care what your game's power-level is. I don't care if you are all playing superheroes who actively pick up entire city blocks and throw them at their enemies. The math behind a game does not, I repeat, DOES NOT have to scale with the strength of the characters and monsters if they were real.

The math of a game only ever has to scale with player understanding.

Friday, January 30, 2015

Triple Comparison: Setting, Art, System, and Layout in P&P RPGs

In this post, I'm going to review three games based on their performance in four areas: setting, art, system, and layout. The games are:

- 4th Edition D&D (Wizards of the Coast)

- Within the Ring of Fire (RAW Immersive Games)

- Dogs In the Vineyard (D. Vincent Baker)

- * = detracts from the game

- * * = maintains game quality

- * * * = adds significant quality to the game

Setting

Not every game needs to come with a setting. Whether it should or not depends on the goals of the game designers. In fact, if all I as a customer will get for setting is another Forgotten Realms or Firefly spin-off, I'd rather the designers save the ink, paper, and time, and hopefully save me a little money. A full-fledged setting that is tacked on at the very end of the game design process is not worthwhile, no matter how in-depth it is.

4e D&D: **

You may be surprised by this, but I think that 4e did setting very tastefully and meaningfully. Technically, the 4e D&D rules are supposed to be setting-independent, but that doesn't mean that there aren't hints dropped all over PHB at a wider world.

Some examples: the gods (1 page, front and back) all have three strictures listed for their worshipers. Every single stricture bullet point is both a little more characterization of the deity, and a potential adventure hook for the players. All of the races have "[Race] adventures" listed, with three example characters and their motivations for going out questing. Each one of these is a window into the larger setting. Some even hook you in with references to fallen empires and ancient kingdoms.

I can appreciate the light sprinkle of setting detail over the (obviously rules-heavy) game that is 4e. It gets the players excited to write their own adventures and start playing. And best of all, in terms of game design, it takes very little work.

Ring of Fire: ***

This is an indie game that you may never have heard of. It was written by an RPG Youtuber that I used to watch religiously before I transitioned over to rpg blogs instead of vlogs. The man is a master of immersion and storytelling grandeur, so I was eager to get the WtRoF Saga book when it came out.

As far as setting goes, there isn't a sour note in the whole 60+ pages of world-building that sit at the end of this 200 page book. Ander went above and beyond any RPG setting expectations, and questioned everything, everything, to make it more fantastical. Day and night cycles? Fantastical. Calendar? Included, and fantastical. Countries and creeds? You get the picture.

This setting must have taken Ander years to put together. That is amazing, and well worth what I paid for the book. I could easily use this setting in another game as well, giving the book even more value to me. But, a time sink like this is intimidating to new players, and sometimes simply not an option for game designers.

Dogs: ***

There's more than one way to impress with your game's setting, however, and Dogs in the Vineyard is the perfect example of a less-traveled road by which to do so. In Dogs, you play the young religious police of a roughly Mormon-equivalent group in still-territorial Utah. The setting is just the 19th century United States, with a few (nicely politically correct) groups added in, plus a little religious or satanic magic too. Nothing too complex, certainly not a world-building undertaking the size of WtRoF.

BUT, the feel of the game is translated so strongly through the introductory descriptions of what being one of "God's Watchdogs" is like, that players can't help but be immersed. Dogs doesn't give you some wide world to go explore, it gives you a deep culture and time period to go explore. This kind of setting has to deliver drama and action on top of its physical locations and societies, because the game is so focused in its scope.

There is far more in Dogs about the interactions between groups than there is about the landscape or technology. That's the drama and action I'm talking about. The game would not be complete without it.

Art

This one will be short and sweet.

4e: ***

I love 4e art. The style and color palette choices are excellent and unlike any other fantasy art I've ever seen. Occasionally, there are pieces from 3.5, but largely, the art is coherent and inspiring (especially the class close-ups, talk about PRETTY). It is professional and it ties the 4e books together neatly.

Ring of Fire: ***

This indie game used indie artists from all over. Although it isn't very coherent, and some pieces are less than professional looking, I as an rpg player appreciate when younger/newer artists contribute to my games. It feels good to know that I am helping them follow their artistic passion by buying these books. And when the art is good, it's really good (I mean, check out that cover! Bad ass.)

Dogs: **

Being another indie game, you can't compare Dogs to something like 4e. There are about a dozen pencil and ink pieces in the rule book that are all coherent and tasteful. They are black and white, which prevents you from seeing the rainbow coats that the Watchdogs have to wear, so that is a small downside. This kind of art is a good balance between a consistent look and feel and an indie budget. You can't always have it all, and using art as an accent rather than a main draw for customers is the right way to go.

System

This is where I could write thousands of words, but instead I'm going to choose one thing about the systems that might otherwise go unnoticed.

4e: **

Check out my Cocktail Weenie post about 4e here. My one addition would be this: when you include literally thousands of bite-sized rules, you are dissuading people from homebrewing their own. This is good for book sales, but may scare away a large customer base of rpg tinkerers. It also puts a huge responsibility on the layout people to make the rules digestible.

Ring of Fire: **

The dice system in WtRoF is a 2d8 system. Double 1s is a crit fail, but there is no crit success. Instead, 8s explode. This creates an open-ended central die mechanic. So while most rolls (and thus most character actions) will be results between 8 and 10, or average performance, you will occasionally get results in the 20s or 30s. It gives players the sense that "anything is possible," but the general grittiness of the rest of the game's mechanics prevent there from being a 4e-style "superhero" effect. Even the task resolution mechanics can add flavor and tone to your game. Which brings us to...

Dogs: ***

Dogs uses a "roll a pool of dice and use them one at a time" system for combat, and it feels like you are gambling. Because you are, essentially. If you play your cards (dice) wrong, you will have screwed yourself over for this encounter. It changes the entire pace of the game, and also emphasizes changes in strategy as opposed to big hits or critical failures. I've never seen another system like it, and I think that adds to the draw of this game. Sometimes, being different in multiple areas is enough to pull some attention in an ever more cluttered market and industry.

Layout

Surprisingly important, let me tell you...

4e: ***

I have never spent more than 15 seconds looking for a rule in 4e D&D. The books are fantastically sectioned off and many rules are color coded (although they did use both red and green, which makes it harder for my colorblind friends to differentiate at-will and encounter powers, that's a no-no). The pages never feel cluttered, the font is clear, and lists are all alphabetical unless another organization system is more intuitive. A+. This is really a matter of time and outside feedback, and it is one of the reasons I like 4e as much as I do. Infinitely better than 3.5 D&D. Also infinitely better than...

Ring of Fire: *

Ouch. This book was written like a stream of consciousness. There are chapter headings, and even the longest table of contents I have ever seen, but those things don't do much good. For example: there are rarely page references within the book when a rule is mentioned. There are key rules that are not denoted in bold or a separate paragraph, so you have to search for them every time you need them, even if you know the exact page. There are no rules for magic in the Saga book, but this was not clear until my friend and I got feedback from the creator, because the Saga book mentions magic in the rules on several occasions, but never references other books or chapters about magic. There are paragraphs that should be split up into three or four smaller paragraphs, so on and so forth.

Not good. I would play WtRoF a lot if it were laid out in a way that could help me and others understand it better. I still bought it, but I don't think game designers should be content with that kind of reaction.

Dogs: **

My one critique of the layout of Dogs is that the margins and type face are so large, that something like character creation takes up over 20 pages. That is a lot of pages to flip through for a set of rules that will always be referenced and used all together. The creators even seemed to acknowledge this, because they put in recap pages at the end of the sections to condense the info down and make sure you got everything.

Rule of thumb: if you have to do that, maybe your layout needs to be clearer.

That being said, the sections and sub-sections are all nicely demarcated, and the table of contents is good. I did a one-shot of this game with a friend who had never seen it before that night, and he picked it up from the rule book just fine, so long as I was there to guide him through some of the sections and make sure he got everything.

Totals

- 4e D&D: 10 stars

- Within the Ring of Fire: 9 stars

- Dogs in the Vineyard: 10 stars

Summary

Setting in a game needs to be deliberate and tasteful. Including a half-ass setting doesn't detract me from the product, but it does detract from my opinion of the company.

Art should be within the game designer's reasonable limits, and including indie artists is a big plus. Hell, I've seen no art games that I liked, but an illustration here or there never hurts.

System is where players' personal tastes will be most influential. System and art put pressures on layout, so make sure you understand what you are getting into. And ask yourself, what do the rules say about my game's setting and tone? Number distributions and dice rolls speak louder than you think.

Layout can be a deal breaker, even for a great game. The simpler your game, the less art, the easier layout is. But this is also where game design time and effort really shine through. Layout is not at all a matter of opinion. Some people will learn to deal with bad layouts if they have played the game enough, but new players will not. And one last thing: don't underestimate font and style. If opening your rpg book is like opening an ancient tome or magical text, points to you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)